Malware Sideloading via MFC Satellite DLLs

Originally, this topic should be part of an analysis of Turla’s COM Kazuar loader, but I decided to write a blog post about this DLL sideloading in general instead. Turla uses this technique since at least 2024 and also in newer campaigns. There are also other threat actors like BRONZE BUTLER who are aware of this method too. This sideloading technique affects all MFC applications that have been created with Visual Studio .NET (2002) - Visual Studio 2010.

What is MFC and What are MFC Satellite DLLs?

Microsoft Foundation Class (MFC), introduced in 1992, is a library of C++ classes that provides developers an easier way to create Windows applications compared to using the appropriate Windows APIs directly. Its goal is to simplify Windows development by offering a framework to handle many common programming tasks on Windows, including GUI management, input/output operations, data handling, and so on. There are many MFC examples for Visual Studio that show how to use these classes.

MFC satellite DLLs, introduced in Visual Studio .NET (2002) (MFC 7.0), are resource-only libraries used to support multilingual user interfaces by holding localized resources separately from the main application. These DLLs contain data such as strings, dialogs and icons for different languages or locales. MFC applications load satellite DLLs at runtime, allowing the core application code to remain unchanged while displaying localized content via the satellite resource DLLs. Satellite DLLs are loaded into the application process as needed based on the user’s language settings.

Sideloading via MFC Satellite DLLs

MFC satellite DLLs are a convenient method to organize multi-language support of an application. However, older MFC applications can be abused to load a malicious DLL instead of the actual satellite DLL. The problem relies in the way how they are loaded together with an option to load a satellite DLL when all methods to find the right language failed. Quote:

To support localized resources in an MFC application, MFC attempts to load a satellite DLL containing resources localized to a specific language. Satellite DLLs are named ApplicationNameXXX.dll, where ApplicationName is the name of the .exe or .dll using MFC, and XXX is the three-letter code for the language of the resources (for example, ‘ENU’ or ‘DEU’).

MFC attempts to load the resource DLL for each of the following languages in order, stopping when it finds one:

- The current user’s default UI language, as returned from the GetUserDefaultUILanguage() Win32 API.

- The current user’s default UI language, without any specific sublanguage (that is, ENC [Canadian English] becomes ENU [U.S. English]).

- The system’s default UI language, as returned from the GetSystemDefaultUILanguage() API. On other platforms, this is the language of the OS itself.

- The system’s default UI language, without any specific sublanguage.

- A fake language with the 3-letter code LOC.

This list describes the order and methods of how the right language is retrieved to load the proper satellite DLL. As can be seen in point 5, there is a “last-resort” option to always load a satellite DLL. This option provides a reliable way to execute a malicious DLL because you typically do not know the victim’s system or user language. You can create a DLL, give it the same name of the MFC application, append the string LOC and it gets loaded by the MFC application when it is run. For example, when you have a MFC application named MyMFCApp.exe, you place your DLL in the same directory and name it MyMFCAppLOC.dll. When you run your MFC application MyMFCApp.exe, your DLL MyMFCAppLOC.dll gets automatically loaded into the process of MyMFCApp.exe and executed.

Under the hood, when a MFC application is executed, there are various initialization routines run before the application’s main entry point is called. One of these routines is CWinApp::InitInstance that in turn calls CWinApp::LoadAppLangResourceDLL. This method is responsible to find the right language in the order shown in the list above. Inside CWinApp::LoadAppLangResourceDLL, the routine that is responsible to load the fake language LOC satellite DLL is called AfxLoadLangResourceDLL. In some cases, the loading of the LOC is contained in subroutines named AfxLoadLangResourceDLLEx or _AfxLoadLangDLL. The following execution paths exist for loading the LOC satellite DLL depending on the MFC version:

CWinApp::InitInstance->CWinApp::LoadAppLangResourceDLL->AfxLoadLangResourceDLLCWinApp::InitInstance->CWinApp::LoadAppLangResourceDLL->AfxLoadLangResourceDLL->AfxLoadLangResourceDLLExCWinApp::InitInstance->CWinApp::LoadAppLangResourceDLL->AfxLoadLangResourceDLL->_AfxLoadLangDLL

Is it really that easy, then? Can I just create a malicious DLL with the right name, place it next to a any legitimate MFC application and it gets loaded when the MFC application is executed?

The answer is yes, but only with older MFC applications. All MFC applications created with Visual Studio .NET (2002) (MFC 7.0.9466.0) - Visual Studio 2010 (10.0.40219.325) are vulnerable to this sideloading technique. The problem is how the supposed resource-only satellite DLLs are loaded in these older MFC versions. The following list shows the Visual Studio versions and how they try to load the LOC satellite DLL.

| Visual Studio Version | Used LoadLibrary Functions for “LOC” Satellite DLL Loading |

|---|---|

| 2026 - 2013 | LoadLibraryExW(..., ..., LOAD_LIBRARY_AS_DATAFILE_EXCLUSIVE | LOAD_LIBRARY_AS_IMAGE_RESOURCE) + LoadLibraryExW(..., ..., LOAD_LIBRARY_AS_DATAFILE) |

| 2012 | LoadLibraryExW(..., ..., LOAD_LIBRARY_AS_DATAFILE_EXCLUSIVE | LOAD_LIBRARY_AS_IMAGE_RESOURCE), LoadLibraryExW(..., ..., LOAD_LIBRARY_AS_DATAFILE_EXCLUSIVE | LOAD_LIBRARY_AS_IMAGE_RESOURCE) + LoadLibraryExW(..., ..., LOAD_LIBRARY_AS_DATAFILE) |

| 2010 - 2002 | LoadLibraryA(...), LoadLibraryW(...), LoadLibraryExW(..., ..., 0) |

As can be seen, MFC applications built with Visual Studio .NET (2002) - Visual Studio 2010 try to load resource-only satellite DLLs with LoadLibraryA/W or LoadLibraryExW with the dwFlags parameter set to 0. This effectively treats a DLL not like a data only source, but as an executable file calling its DllMain method. Since Visual Studio 2012, the code has been changed to use LoadLibraryExW with the dwFlags parameter set to LOAD_LIBRARY_AS_DATAFILE_EXCLUSIVE | LOAD_LIBRARY_AS_IMAGE_RESOURCE or LOAD_LIBRARY_AS_DATAFILE, finally treating these DLLs are data-only libraries.

As a result, all MFC applications created Visual Studio .NET (2002) - Visual Studio 2010 are vulnerable to this sideloading technique. It also does not matter if an application has been compiled with static MFC libraries or with a shared MFC DLL (e.g. mfc80.dll, mfc100.dll, etc.). In the first case, the DLL loading is done in the statically compiled MFC initialization routines, in the latter case it is done by the linked MFC library. Of course, a 64-bit malware fake satellite DLL can only be loaded by a 64-bit MFC application. The same goes for 32-bit files.

Proof Of Concept

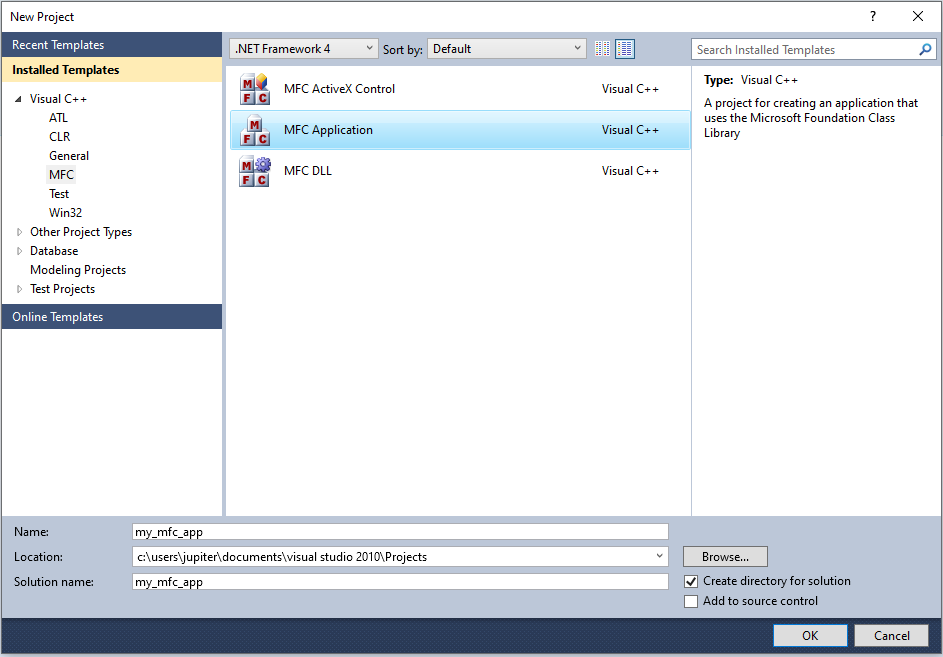

Let us get a copy of Visual Studio 2010 (officially not available for download anymore) to create a POC MFC application. To create a DLL with code that is loaded as a LOC satellite DLL you can use any other compiler.

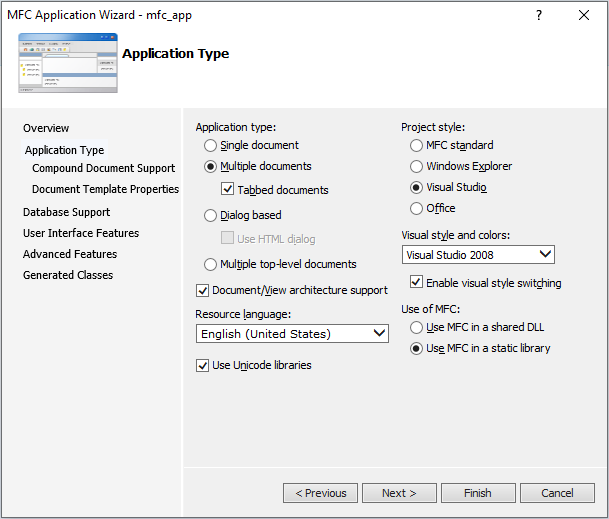

For the MFC application, we can just use the standard MFC application template and compile a 64-bit release version with statically linked MFC libraries:

As a 64-bit satellite DLL, we create a simple code that prints a debug message with the file path of the process from where it was loaded from (via LoadLibraryW):

#include <windows.h>

#include <stdio.h>

BOOL WINAPI DllMain(HINSTANCE hinstDLL, DWORD fdwReason, LPVOID lpvReserved)

{

if (fdwReason == DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH)

{

char processPath[MAX_PATH];

DWORD pid = GetCurrentProcessId();

DWORD pathLen = GetModuleFileNameA(NULL, processPath, MAX_PATH);

if (pathLen == 0) {

strncpy_s(processPath, MAX_PATH, "<unknown process path>", _TRUNCATE);

}

char outputString[256];

int len = _snprintf_s(outputString, sizeof(outputString), _TRUNCATE, "Hello from DLL inside process: %s (PID: %lu)\n", processPath, (unsigned long)pid);

if (len > 0) {

OutputDebugStringA(outputString);

}

}

return TRUE; // Causes the DLL to be loaded and executed. However, this also makes MFC think there is a valid satellite DLL being loaded and thus it

// is also treted like this. This may cause some implications for subsequent routines which, however, might be also advantageous at least

// for malware. For example, if the MFC application usually displays a GUI, it may not be shown. Also, depending on the malware's purpose,

// it might be a wanted behavior when the DLL stays loaded in the MFC application.

// In case of "return FALSE;", the DLL gets loaded, executed and unloaded again. This does not cause any implications for the MFC

// initializations routines and thus the MFC application. But a malware module does not stay in the process which might not be wanted.

}

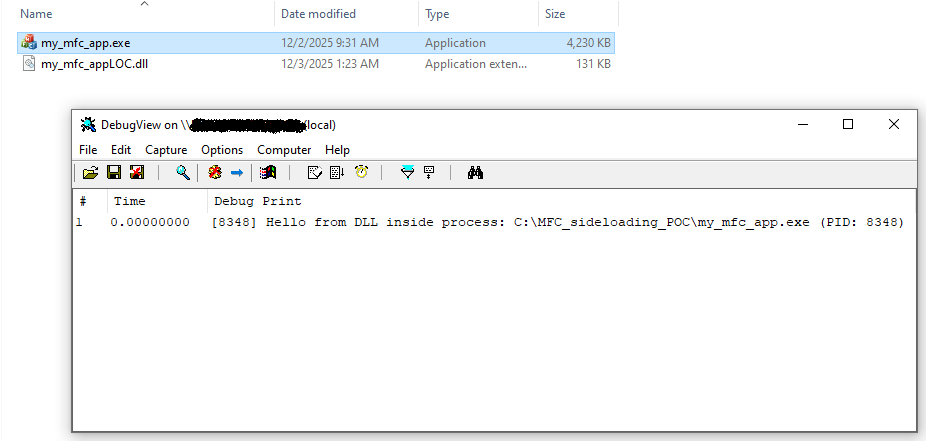

After we have compiled our MFC application my_mfc_app.exe, we place the compiled DLL into the same directory and rename it to my_mfc_appLOC.dll. The result after executing my_mfc_app.exe can be seen in the following screenshot:

We can observe that the DLL code was executed as shown by DebugView. However, because the MFC initialization routines treated the DLL as a satellite DLL, the GUI of the MFC application did not display (see return value comment in DLL example code).

To sum up, you can give a vulnerable MFC application any name, place a (malicious) DLL the same name with the string LOC appended in the same directory and it gets loaded and executed when the application is run. Also, the LOC suffix does not need to be case-sensitive. For example, you can rename a legitimate MFC application mal.exe and your (malicious) DLL malloc.dll and it still gets successfully loaded.

How many potentially vulnerable MFC applications exist?

I have made a Yara rule that tries to identify MFC EXE files that are created by the vulnerable Visual Studio / MFC versions. The rule searches for both, statically compiled and shared library, MFC executables. I selected to include only signed files, as these are the most likely ones abused by malware.

Yara rule:

import "pe"

rule sideload_vulnerable_mfc_application

{

meta:

author = "Dominik Reichel"

description = "Detects satellite DLL sideloading vulnerable MFC applications"

date = "2025-11-30"

reference = "https://r136a1.dev/2025/12/03/malware-sideloading-via-mfc-satellite-dlls/"

strings:

$a0 = ".?AVAFX_MODULE_STATE@@"

$a1 = "MFC"

$a2 = "Microsoft Visual C++ Runtime Library"

$a3 = "GetUserDefaultUILanguage"

$a4 = "GetSystemDefaultUILanguage"

condition:

uint16(0) == 0x5A4D and

uint32(uint32(0x3C)) == 0x00004550 and

pe.is_signed and

pe.characteristics & pe.EXECUTABLE_IMAGE and not

pe.characteristics & pe.DLL and

(

(

pe.imports("mfc70.dll") or

pe.imports("mfc70u.dll") or

pe.imports("mfc71.dll") or

pe.imports("mfc71u.dll") or

pe.imports("mfc80.dll") or

pe.imports("mfc80u.dll") or

pe.imports("mfc90.dll") or

pe.imports("mfc90u.dll") or

pe.imports("mfc100.dll") or

pe.imports("mfc100u.dll")

) or (

all of ($a*)

)

)

}

With this Yara rule, there have been about 10k samples found by a Virustotal Retrohunt scan for the last 365 days. However, if we additionally take into account non-signed executables, the real number of MFC applications is greater.

Detection

Malicious behavior is often difficult to identify, as it is in this case. One idea would be to:

- Monitor for DLL loading (kernel-mode notification callbacks, user-mode monitoring DLL, …)

- Check if the process is a (vulnerable) MFC application (see Yara rule above for ideas)

- Check if the DLL file path is in the same directory as the MFC application

- Check if a loaded module ends with “loc” (lowercase actual name) -> Might be unreliable as there are likely also legitimate DLLs with such a suffix

- Check if the loaded module has the following resource-only contradictory PE characteristics:

- AddressOfEntryPoint is not 0

- Contains executable sections

If these points apply, block the DLL from loading or create an alert as it is most likely a fake malicious satellite DLL. However, in reality it might be more difficult to implement a reliable solution that does not cause any FP hits.

Conclusion

MFC satellite DLLs offer a comfortable way to structure support multiple languages for an application. However, since its introduction in Visual Studio .NET (2002) / MFC 7.0.9466.0 und up until Visual Studio 2010 / 10.0.40219.325, the implementation in the MFC initialization routines is unsecure. You can use any MFC application compiled with these vulnerable versions and place a malicious DLL with the same name and the string LOC (case-insensitive) appended to it in the same directory and when the application is run it gets executed. This is because the option to always load a satellite DLL by naming it ...LOC.dll is using LoadLibraryA/W or LoadLibraryExW(..., ..., 0), thus treating the supposed resource-only satellite DLL as an executable file and not as a data-only source. Starting from Visual Studio 2012 / MFC 11.0, this vulnerability has been closed.

This DLL sideloading technique shows how a feature developed during a time when security was not so much of a concern during development, may be misused many years afterwards. There are literally thousands of legitimate (and signed) executables that can be and that are already misused for malware loading.

R136a1

R136a1